In 1906, the biggest threat to young athletes was death, and one of the nation’s most-loved sports, football, was on the verge of being eliminated. According to CNN, by the end of 1905, a total of 18 football players, both college and amateur, had died of sports-related injuries. Despite the increasing number of fans, there was a large movement to ban the sport.

The movement was intensified when The New York Times ran an editorial expressing concern over "Two Curable Evils" in American life: lynching’s and football.

Then, the President stepped in.

President Theodore Roosevelt invited 13 football representatives to the White House to discuss how to improve safety. These meetings created The National Collegiate Athletic Association or the NCAA. Its purpose was “to protect young people from the dangerous and exploitive practices of the time.”

Almost 112 years later, the threats to student-athletes have changed, escalated and become more complex under an expanding economy.

While the NCAA’s revenue has reached an all-time high, the scrutiny of the association has risen equally. Athletes, sports analysts and media members have questioned the NCAA on where its money is going, why student-athletes are not being paid and what purpose the NCAA even serves.

Between FBI investigations, recruiting scandals and Supreme Court hearings, the purpose of the NCAA has blurred. Its core values emphasize the balance of athletics, social and academic experiences while also building a community around intercollegiate athletics.

READ MORE: The NCAA has seven Core Values.

So, is the NCAA still holding true to its purpose and core values?

Here are the facts.

Where Does The Money Go?

Last year, the NCAA passed the $1 billion dollar mark in annual revenue for the first time ever.

Ever heard of March Madness? That’s the source of most of that money.

According to the NCAA website, Division I Men’s Basketball Championship television coverage and marketing rights produced $821.4 million for the NCAA while $129.4 million came from championship ticket sales.

As a tax-exempt organization, the NCAA is unable to personally profit from any of its revenue. It must put this money back into its purpose: protecting student-athletes in various ways.

Mallory Franklin, a former Baylor University football player, voiced his support of the NCAA protecting student-athletes.

“(The NCAA) informs us on how they protect us and how to keep ourselves protected," Franklin explained. "They tell us everything we need to know as far as amateurism, Title IX issues, how to conduct yourself in classrooms and things of that nature. They tell you how to prevent yourself from getting into any issues, and I think they’re doing a terrific job at that.”

The NCAA also funds many programs that directly support the educational, financial, and health and safety needs of student-athletes.

The benefits for student-athletes are broken down further under each category.

For example, in 2015 Baylor opened the Beauchamp Athletics Nutrition Center, which Franklin agreed to be one of the best improvements in athletic resources.

“The nutrition center, that was great," Franklin said. "You walked in, and you would find something to eat. It’s not like your average dining hall.”

Brianna Richardson, a former Baylor track and field athlete, also agreed that having the nutrition center made a big difference. She emphasized how receiving a brand new track-and-field facility in 2015 added to her overall athletic experience.

“I know there are schools out there where they’re just telling kids ‘eat what you want, do what you want but just make sure you’re ready to compete when it’s time to compete.’ So, having those nutritionists here to educate us on what we should be putting in our body and what we shouldn't’ be putting in our body was very beneficial," Richardson said. "Plus, being able to move into that huge nice (track and field) facility and we have everything there, all in one place, was really amazing.”

Along with these benefits, the NCAA dedicates its revenue specifically to the needs of student-athletes. A majority goes to scholarships, or compensation, something for which the NCAA is heavily scrutinized.

Franklin walked on to the Baylor football team in 2014 and earned a full scholarship in 2016.

“It’s not common that guys earn full scholarships," Franklin said. "Some guys got theirs earlier than others and I was the last to receive one but I definitely feel like I earned mine as fair as anybody else.”

Richardson earned a full scholarship upon entry to the university.

“Throughout my high school career, I competed in different meets at a very high level which gave me the opportunity to be recruited by numerous D1 schools across the country," Richardson explained. "I do believe the way it was presented to me was pretty fair.”

Last year, $210.8 million went to sport sponsorships and scholarship funds distributed to Division I schools. Money is also dispersed into catastrophic insurance plans, drug-testing, sports injury research and minority opportunities.

This leads to the NCAA’s biggest scrutiny.

Are Student-Athletes Getting Paid?

The most heated argument against the NCAA is the idea of paying athletes. Aside from broadcast rights and ticket sales, individual athletes play a major role in total revenue.

According to ESPN, in 2013 college basketball analyst Jay Bilas used his platform to shine light on how the NCAA was allegedly taking advantage of individual players through jersey sales. Texas A&M former star quarterback and Heisman trophy winner, Johnny Manziel, reportedly brought in $37 million worth of exposure for the school. After the controversy, the NCAA removed jersey sale profits.

In the same year, the National College Players Association and Drexel University released a study that concluded an FBS football player is worth $137,357 per year, and the average men's basketball player is $289,031 per year. The study was based on how professional athletes are paid. In the NBA, players receive 50-percent of all revenue, and in the NFL players receive 46.5-percent of all revenue.

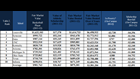

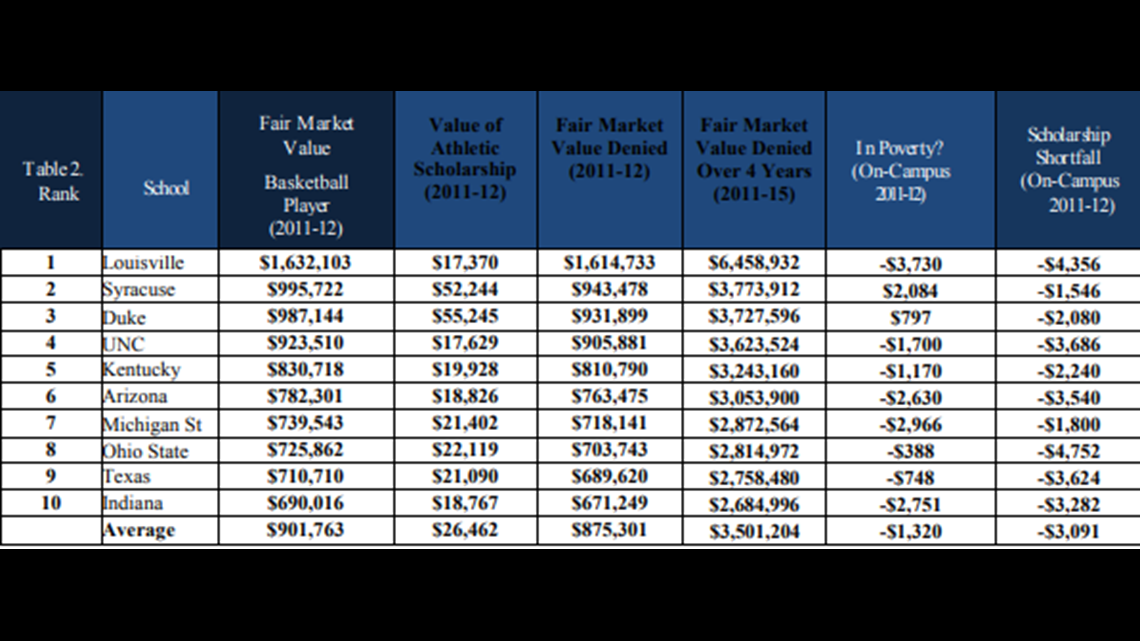

Top 10 schools where basketball players are worth the most:

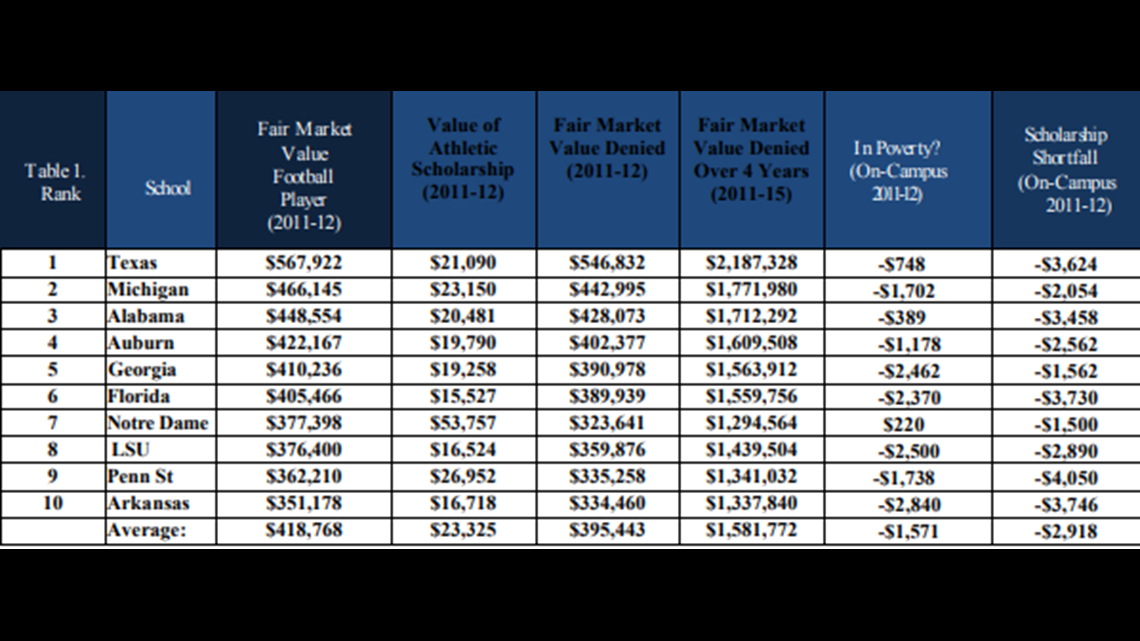

Top-10 schools where football players are worth the most:

IN DEPTH: Read the full study here.

Ranking the percentage that professional athletes get paid to how the NCAA performs is not completely realistic, considering all the avenues the NCAA covers with the revenue it receives.

While the NCAA just passed the $1 billion dollar mark, according to Forbes, the NBA totaled $5.9 billion in revenue last season while the NFL was projected to surpass $13 billion in 2016. Its expenses are defined by player and coach income while the NCAA defines its expenses under a non-profit self-sufficient structure.

According to the NCPA and Drexel study, in comparison to money student-athletes are worth, an average scholarship in 2015 for a men’s basketball player was $38,246. For FBS football, it was $36,070.

Although athletes do not receive a formal paycheck, some do receive compensation for the hours they put in, and the NCAA has worked to expand that financial support.

According to USA Today, at the 2015 annual NCAA convention, the five largest conferences in the NCAA voted to expand what Division I schools could provide under an athletic scholarship. The vote was represented by 65 schools and 15 athlete representatives from the Atlantic Coast, Big 12, Big Ten, Pacific-12 and Southeastern conferences.

The vote officially redefined an athletic scholarship so it could cover more than the traditional tuition, room, board, books and fees. The expansion allowed for cost-of-attendance scholarships to pay for items including transportation and other personal expenses.

In other words, student-athletes could receive cash stipends.

Both Franklin and Richardson received stipends while at Baylor. They each had different views.

“I knew my bills and all that of that and I had enough spending money for the month so I believe (the stipend) was enough to cover all of my expenses,” Franklin said.

Richardson believed her freshmen year stipend was sufficient enough to cover expenses; but after moving off campus, although her stipend did increase, she did not believe the amount was reasonable.

“Later down the road when I moved off campus and had to pay for rent, utilities, car payment, phone bills, other bills, I believe we could have got a little more money," Richardson said. "Especially since we weren’t able to live off campus and have a meal plan.”

As a walk-on, Franklin did not receive a stipend until two years after being committed to the Baylor football team. He explained that although he had enough financial aid to cover the basic school expenses, it was hard to cover personal expenses.

“It was definitely tough," Franklin said. "I had support from my mother whenever she could, but I made sure to get a meal plan that way I could eat. But, as far as having any extra money to spend on for bills or leisure, my mother really helped me."

Franklin said he tried to pick up summer jobs in the off season and depended on refund checks that sometimes did or did not suffice.

“I was a full-time student-athlete, so I didn’t have time to work during the season," Franklin said.

When asked about how the NCAA could specifically help student-athletes more financially, Richardson said stipends should be based on the average cost of living for a college student. She also mentioned that the NCAA should take into consideration student-athletes who don’t have help from their families.

USA Today reported that the vote to expand cost-of-attendance scholarships followed an antitrust lawsuit, where the NCAA found there was an average difference of about $2,500 between the value of a current athletic scholarship and the value of an athletic scholarship based on cost of attendance.

This decision came after years of discussion within the association which included concerns over how programs would fund them.

There was a downside. The cost-of-attendance scholarship expansion was ruled optional and not as a requirement. The vote to make it a requirement was shot down by one vote.

Franklin voiced that all student-athletes should be rewarded.

“Everybody should be rewarded whether they are on scholarship or if they’re a walk-on. At the end of the day everybody is held to the same standard, the same responsibilities.”

He did also mention how rewarding all student-athletes could decrease opportunity for walk-ons. Creating a budget would initially put limits on how many walk-ons a team could pay for.

But, all’s fair in democracy, right?

Other than working towards more compensation for student-athletes, the NCAA has also worked towards a fairer governing structure. This vote was actually the first time student-athletes were granted a voice at the annual NCAA convention, held in Washington, D.C in 2015. This was one of the first steps in improving protection through autonomy.

While attending Baylor, Franklin and Richardson never got the opportunity to speak to an NCAA representative about their concerns.

“With the NCAA being such a broad variety of student-athletes, a broad variety of universities, different circumstances, I feel like they should do something to where they bring together numerous athletes from different places to give their opinion. If the athletes feel like they have a voice, they’d be more open to speaking up,” Richardson said.

In the past few years, the NCAA has increased representation at the 2016 and 2017 NCAA convention. According to SCAC Sports, a record 22 student-athletes attended the 2016 convention from this division. This was made possible through the NCAA Division III Strategic Initiative Grant.

Threats against student-athletes are evolving, but through changes in governing and convention conversations, the NCAA is evolving as well.

From What is The NCAA Protecting Student-Athletes?

One of the major differences between 1906 and 2018 is money.

Within the past two years, the FBI has stepped in to help the NCAA with two of its growing issues: fraud and corruption.

The FBI has centered its investigation around recruitment tactics for NCAA basketball players, who already receive a large percentage of NCAA scholarships and produce most of its revenue.

These investigations involve multiple athletic companies, schools, coaches and players. Among the many involved are Adidas, the ASM Sports agency and huge athletic programs such as Alabama, Texas and Louisville are just a few to name. Players who have already been drafted to the NBA like Markelle Fultz and Kyle Kuzma, are on the list as well.

The total money paid out in these fraud and corruption cases surpasses thousands of dollars.

An executive at Adidas is accused of funneling money to high school athletes and their families to attend Adidas-sponsored schools. Brian Bowen, a top recruit for Louisville, accepted thousands of dollars in travel expenses and ultimately toppled Louisville’s basketball program. The NCAA was already sanctioning them for recruitment violations including a sex scandal.

Fultz and Kuzma were both reportedly bribed by ASM Sports agents. Fultz was allegedly given $10,000 before his one season at University of Washington. The money was reportedly offered to persuade him to sign with ASM Sports after going professional. He did not end up signing. Kuzma also received nearly $10,000 while attending the University of Utah.

The list goes on.

The main point here is exploitation.

Both Franklin and Richardson expressed their concerns on how young athletes are being unfairly persuaded during the recruiting process before signing their name on the dotted line.

“I wasn’t a highly-recruited athlete but I know now that I didn’t know a lot. You don’t know what the rules are because 9 time out of 10 when a person puts a piece of paper in front of you and you sign it, you’re not going to read it, when you’re 18, you’re not,” Franklin said.

Franklin also voiced that in the mist of opportunity, young athletes are vulnerable.

“(The NCAA) should watch out for that because have they been educated on what they can and cannot accept?" Franklin asked. "At the end of the day, they’re taking advantage of kids. (They’re thinking) ‘I got to make my mama happy, I got to take care of my mama, I got to get this bag so I’m going to sign whatever so we can be alright.’ They need to keep a big eye out for that.”

Richardson explained how the recruiting process has evolved over the years, and it does not seem that the NCAA is doing its job to keep up.

“There a lot of things you can do today that you couldn’t do five to 10 years ago to get a kid to come to a certain school," Richardson said.

She also shared the same idea as Franklin, expressing how young athletes are vulnerable and it’s the NCAA’s job to do more to protect them.

“With the NCAA, as far as protecting kid’s rights, they don’t really look into it soon enough and it destroys that student-athlete that was 16 or 17-years old being recruited out of high school," Richardson said. "They’re hearing these things like ‘people aren’t getting caught, I’ve been doing this for years,’ so those are the things they want to hear that are going to persuade them to going to that specific university. There is no reason why the NCAA is such a big, big, big organization and they can’t control that.”

Both of these former student-athletes felt passionately about this situation, but they also both expressed that the NCAA has been protecting student-athletes pretty well otherwise.

Is the NCAA holding true to its standards?

The dangerous and exploitive practices against student-athletes are not the same as 100 years ago.

As threats towards student-athletes evolve, the association has been forced to evolve as well.

The NCAA has shown willingness to change and adjust. The association has presented itself in court, revisited the idea of autonomy, compensation and involved the FBI to help protect student-athletes from exploitation.

The major concern that remains is continuing to balance a student-athlete’s overall experience through athletic, social and academic advancements.

Franklin and Richardson expressed that they did enjoy the experience of being student-athletes.

“We had tutoring, our advisors were amazing and I definitely feel like I gained tools in life. Playing football I believe builds character. We had community service and some guys, when they became seniors, they got them suites. There are a lot of benefits, besides finances, as being a student-athlete,” Franklin said.

“The relationships I’ve formed with different people that I’ve met along the way, not even only friends that I’ve made but associates that I’ve made. I feel like the environment I was put it was family-oriented,” Richardson said.

Athletics-wise, the NCAA continues to improve facilities and access to physical protection. Socially, the NCAA struggles with the question of paying student-athletes what they’re worth. And academically, the classroom for student-athletes also hangs in the balance.

At the end of each conversation, both former student-athletes reiterated that the NCAA should work on compensating student-athletes more fairly.

“What can you do better to help us, what can you do more, what can you add to the NCAA programming where it’s not so hard to be a student-athlete? Because being a student-athlete is supposed to be fun,” Richardson said.

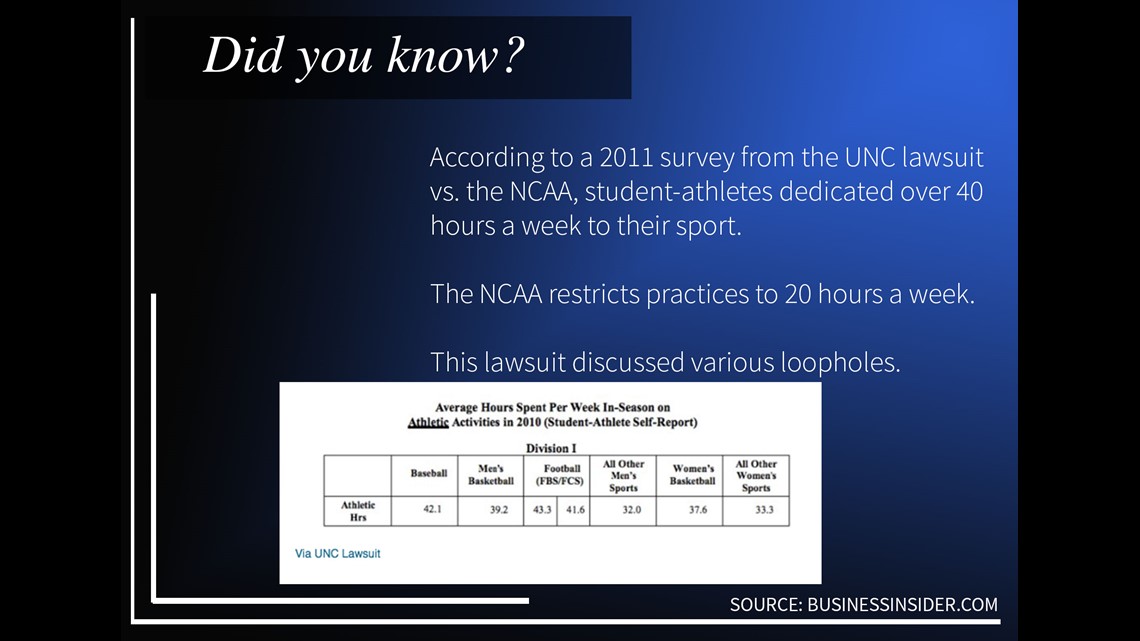

They both also expressed that the time they spend as athletes affects the time they have for class, time to eat and money they spend on living accommodations when having to stay over summer or holidays.

Richardson voiced that all athletes experience these difficulties and should be compensated equally.

“It needs to be equal distribution to all those across the entire NCAA and that will most-likely help most of the controversies and other things going on right now.”

Franklin emphasized on the extra time student-athletes sacrifice over the summer.

“I’m not saying throw money at them but reward those guys for being there because it was voluntary until you signed to be on team, now you’re a member of the team and you have these expectations,” Franklin said.

Each day the NCAA has to find ways to accommodate three divisions, 24 sports, 90 championships and 1,100 schools and 460,000 athletes across the United States. Those numbers continue to grow.

With each obstacle thrown the NCAA’s way, the reactions, the changes and the facts hold true to its purpose and core values.

Is there room for improvement? Always.

Last question.

Is the NCAA still a necessary entity to protect student-athletes?

You be the judge.